UC Davis scientists develop wheat that produces its own fertilizer

Scientists at the University of California, Davis, have developed wheat plants that stimulate the production of their own fertilizer. This breakthrough could reduce pollution and lower production costs for farmers worldwide.

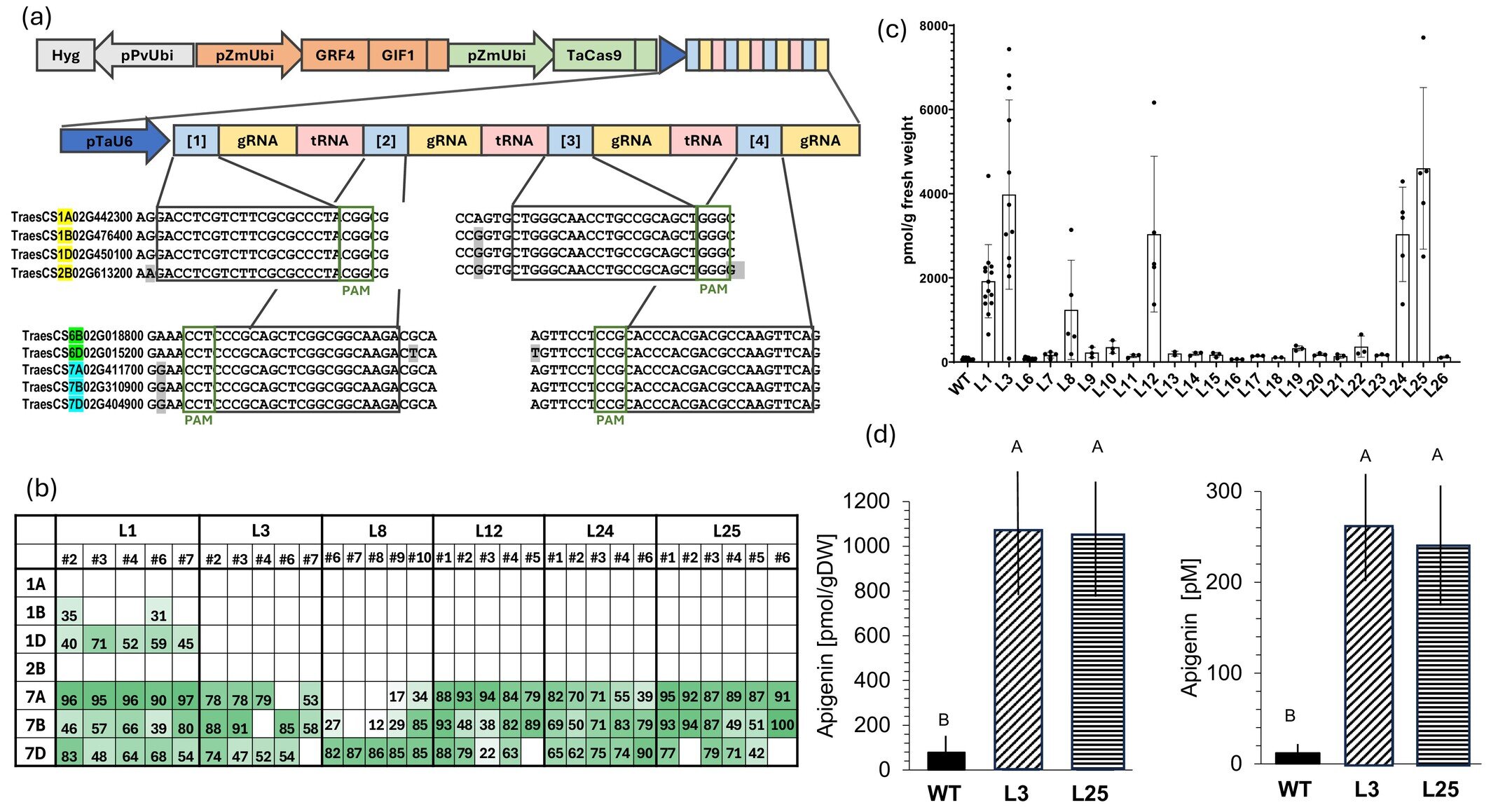

The research team, led by Eduardo Blumwald, a professor in the Department of Plant Sciences, used the gene-editing tool CRISPR to enhance the plant’s natural production of apigenin, a flavone compound. Excess apigenin released into the soil promotes the formation of bacterial biofilms, which create a low-oxygen environment that allows microbes to fix nitrogen from the air into a form plants can use.

The findings, published in the Plant Biotechnology Journal, build on earlier work by Blumwald’s group in rice and may eventually be extended to other cereals.

Wheat is the world’s second-largest cereal crop by yield and the single biggest consumer of nitrogen fertilizer, accounting for roughly 18% of global use. Fertilizer production topped 800 million tons in 2020, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. Yet plants absorb only 30–50% of applied nitrogen, with the remainder polluting waterways or contributing to greenhouse gas emissions.

Blumwald said the new approach avoids decades of unsuccessful attempts to give cereals root nodules like legumes, where nitrogen-fixing bacteria naturally thrive. Instead, the modified wheat creates soil conditions that allow bacteria to perform nitrogen fixation outside the plant.

In greenhouse experiments, the gene-edited wheat produced higher yields under low nitrogen conditions compared with conventional plants. If applied at scale, the technology could ease input costs. U.S. farmers spent nearly $36 billion on fertilizers in 2023, according to the Department of Agriculture. Blumwald estimates that cutting fertilizer use by even 10% across the nearly 500 million acres of cereals planted in the United States could save more than $1 billion annually.

The potential benefits may be most significant in developing regions where fertilizer is scarce or unaffordable. “In Africa, people don’t use fertilizers because they don’t have money, and farms are small,” Blumwald said. “Imagine planting crops that stimulate bacteria in the soil to create the fertilizer they need, naturally.”

The study, Increased Apigenin in DNA‐Edited Hexaploid Wheat Promoted Soil Bacterial Nitrogen Fixation and Improved Grain Yield Under Limiting Nitrogen Fertiliser, was authored by Hiromi Tajima and colleagues and published in August 2025.

Enjoyed this story?

Every Monday, our subscribers get their hands on a digest of the most trending agriculture news. You can join them too!

Discussion0 comments