Researchers map Denmark’s environmental microbiome for the first time

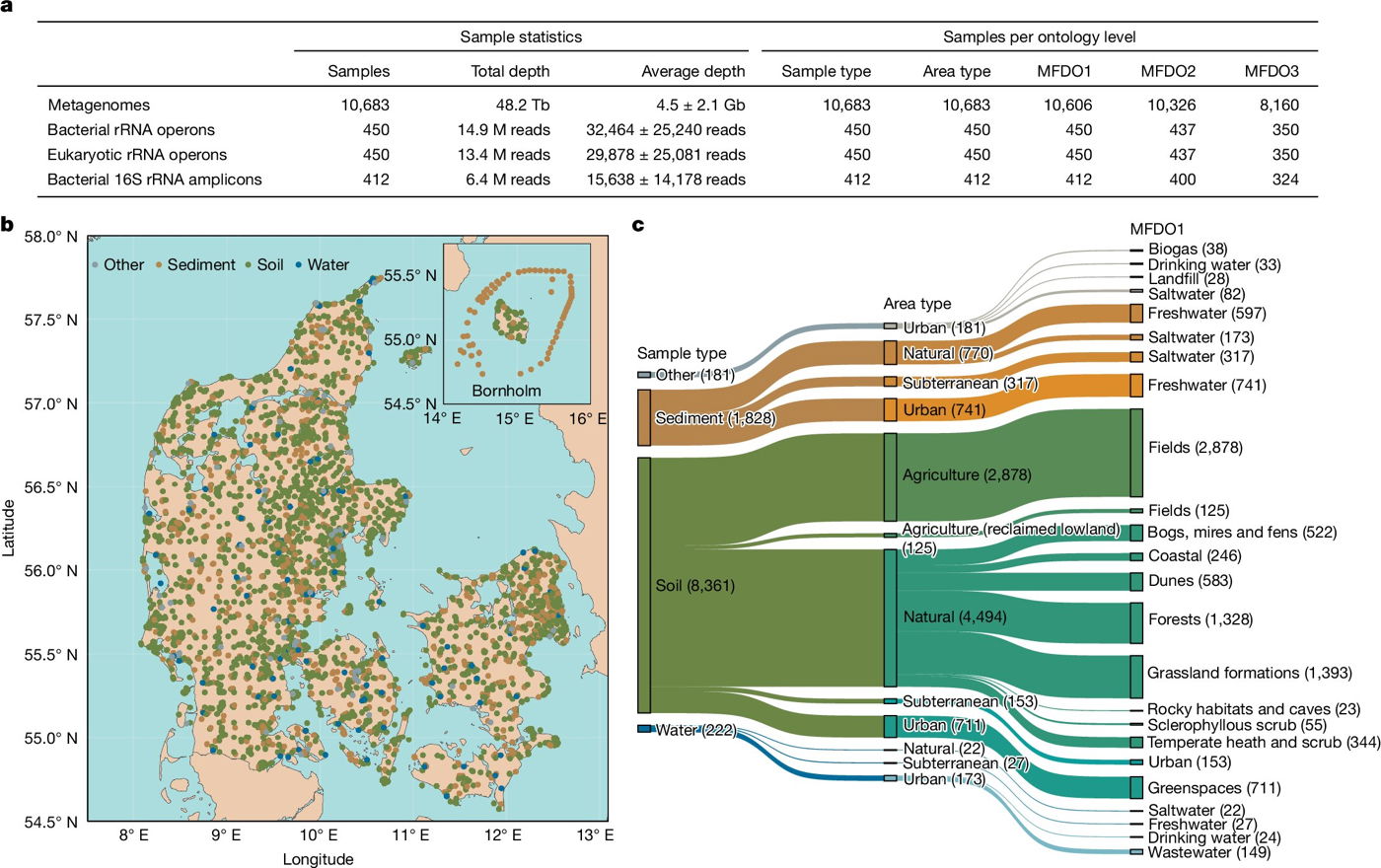

An international team of scientists has mapped the environmental microbiome of an entire country for the first time, creating a high-resolution atlas of microbial life across Denmark. The project, led by Aalborg University with contributions from the University of Vienna, analyzed more than 10,000 soil and environmental samples nationwide and was published in Nature under the title Microflora Danica.

Samples were collected at an average spatial resolution of about four square kilometres, producing what researchers describe as an unprecedented overview of the country’s microbial diversity and function. The dataset provides insight into how microorganisms respond to land use, agriculture and environmental disturbance at a national scale.

Scientists from the University of Vienna played a central role in analysing nitrifiers — microorganisms that drive key steps in the global nitrogen cycle. These organisms determine how long nitrogen from fertilizers remains available to crops and when it is converted into forms that pollute waterways or escape into the atmosphere.

The study shows, for the first time, the nationwide distribution of nitrifiers in soils. It also highlights major knowledge gaps: two of the most widespread groups — the TA-21 lineage of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and comammox Nitrospira clade B — have no cultivated representatives. As a result, they cannot yet be studied directly in laboratory settings despite dominating large areas of agricultural and natural soils. The researchers also identified strong evidence for previously unknown and uncultivated groups of nitrite-oxidizing bacteria.

The findings carry particular weight for Denmark, where roughly two-thirds of land is used for agriculture. Intensive fertilizer use leads to significant nitrogen losses into groundwater, rivers and coastal waters, while also contributing to emissions of nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas. Different nitrifiers vary in how much nitrous oxide they produce and how they respond to nitrification inhibitors added to fertilizers, making their distribution critical for environmental management.

Researchers say the atlas could help make agriculture more targeted and sustainable by aligning fertilizer strategies with the microbial communities present in soils. Over time, this could reduce nutrient losses, limit water pollution and cut greenhouse gas emissions.

Beyond agriculture, the study shows that human disturbance leaves a clear microbial signature. Intensively managed habitats tend to have high local diversity but appear more homogenized at the national level. Less disturbed ecosystems retain greater overall microbial diversity. The authors suggest such “microbial fingerprints” could eventually be used to assess the success of habitat restoration projects.

The implications extend beyond Denmark. Austria faces similar challenges related to farming intensity, nutrient management and water protection. According to researchers involved in the study, the Danish atlas provides a model for how national-scale microbiome data could inform environmental policy elsewhere, from fertilizer optimization to estimating soil-based greenhouse gas emissions.

The authors argue that incorporating microbiome data into land-use planning and climate strategies will be essential as countries seek to balance agricultural productivity with environmental protection.

Enjoyed this story?

Every Monday, our subscribers get their hands on a digest of the most trending agriculture news. You can join them too!

Discussion0 comments