Texas engineers develop hydrophobic sand layer to cut irrigation losses during drought

Researchers at Texas A&M University have developed a chemically modified sand designed to help crops retain moisture during drought, offering a potential new tool for water-stressed agricultural regions.

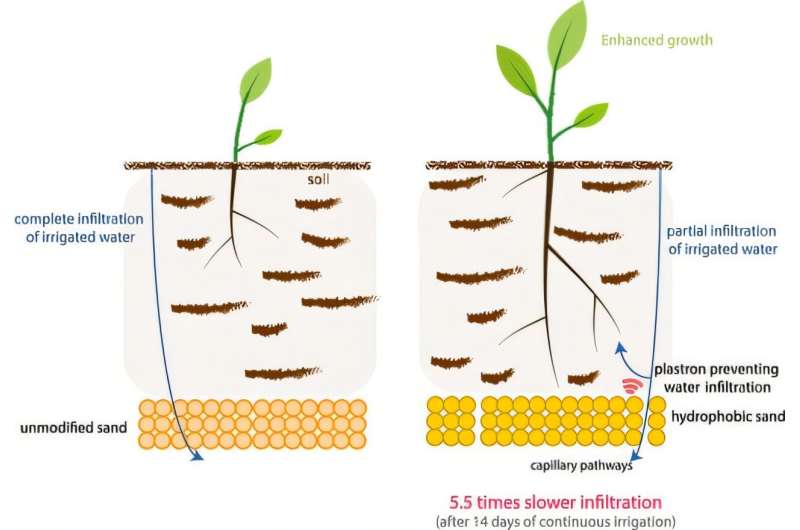

The technique involves altering the surface chemistry of ordinary sand to make it hydrophobic, or water-repellent. When placed in a thin layer just below plant roots, the modified sand slows the downward drainage of irrigation water, allowing moisture to remain in the root zone for longer periods.

The research, published in the journal ACS Omega, coincides with the increasing frequency and severity of droughts worldwide. The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction estimates that the number and duration of droughts have increased by nearly 30% since 2000, putting additional pressure on irrigation systems, particularly in hot and arid regions.

“In recent years, drought has become a bigger concern, especially in southern states like Texas,” said Mustafa Akbulut, a professor in the Artie McFerrin Department of Chemical Engineering at Texas A&M. “Irrigation is one of the largest uses of water in agriculture, so improving water-use efficiency is critical.”

To create the hydrophobic material, the engineers modified the surface of silica—the primary building block of sand—by chemically bonding it with organosilane compounds. This process replaces reactive hydroxyl groups on the sand surface with a water-repelling layer less than two nanometers thick, thousands of times thinner than a human hair.

The researchers tested the concept under controlled conditions using tomato plants. Containers were filled with layers of soil and sand, with some including a layer of modified sand beneath the root zone. All samples received the same amount of irrigation, and drained water was collected and measured.

The results showed that containers with the hydrophobic sand layer retained more water and supported stronger plant growth. Tomato seedlings grown with the modified sand exhibited roughly twice the growth of those grown in unmodified soil, according to the study.

Akbulut said the approach is designed to minimize disruption to existing soil systems. The team envisions an injection method that would create a two- to three-inch hydrophobic layer beneath plant roots, enhancing moisture retention without significantly altering soil chemistry where roots actively grow.

The technology could be particularly valuable for sandy soils, which drain quickly and often require frequent watering and fertilization. While the work is still at an experimental stage, the researchers say the modified sand is chemically stable and could be adapted for field use with further development.

Enjoyed this story?

Every Monday, our subscribers get their hands on a digest of the most trending agriculture news. You can join them too!

Discussion0 comments