Higher water levels could turn cultivated Arctic peatlands into a carbon sink

Raising groundwater levels in cultivated peatlands in northern climates could significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and, in some cases, turn agricultural land into a net carbon sink, according to new research conducted in Arctic Norway.

Peatlands are among the world’s largest natural carbon stores because waterlogged, oxygen-poor conditions slow the decomposition of dead plant material, allowing carbon to accumulate over thousands of years. When peatlands are drained for farming, oxygen enters the soil, accelerating microbial activity and releasing long-stored carbon as carbon dioxide (CO₂).

While the climate effects of draining peatlands have been widely studied in temperate regions, far less is known about peat soils at high latitudes, where low temperatures, short growing seasons and long summer days shape biological processes.

Researchers from the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (NIBIO) sought to close that gap through a two-year field experiment in the Pasvik Valley in Finnmark, Northern Norway. The study, published in Global Change Biology, examined how water levels, fertilization and harvesting affect emissions of CO₂, methane and nitrous oxide from cultivated Arctic peatland.

“From studies in warmer regions, we know that raising groundwater levels in drained peatland often reduces CO₂ emissions,” said Junbin Zhao, a researcher at NIBIO and lead author of the study. “But wetter conditions can also increase methane, and under some circumstances nitrous oxide, so the total climate effect is not straightforward.”

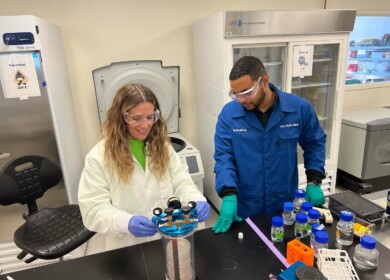

Between 2022 and 2023, the researchers monitored greenhouse gas fluxes at NIBIO’s Svanhovd research station using automated chambers that measured emissions several times a day throughout the growing season. Five experimental plots reflected typical agricultural management practices, with varying groundwater depths, fertilizer inputs and harvest frequencies.

The results showed that well-drained peatland emitted large amounts of CO₂, comparable to cultivated peat soils further south in Europe. When groundwater levels were raised to between 25 and 50 centimeters below the surface, however, CO₂ emissions fell sharply.

“At these higher water levels, methane and nitrous oxide emissions were also low,” Zhao said. “Under such conditions, the field absorbed slightly more CO₂ than it released.”

The researchers found that high groundwater reduced oxygen availability in the soil, slowing peat decomposition. Although wetter conditions also reduced plant activity and CO₂ uptake, the net balance still improved. In northern regions, long summer days amplified this effect by extending the number of hours during which photosynthesis outweighed respiration.

Temperature emerged as a critical constraint. When soil temperatures exceeded about 12 degrees Celsius, microbial activity increased, raising both CO₂ and methane emissions. “This means the climate benefit of high water levels is strongest in cool environments,” Zhao said, adding that future warming could weaken the effect.

Farm management practices also played a role. Higher fertilizer application increased grass growth but did not significantly change greenhouse gas emissions in the trial. Harvesting, by contrast, removed carbon stored in plant biomass. Frequent cutting reduced the amount of carbon retained in the system, potentially leading to long-term losses from the peat layer even when water levels were kept high.

The study also documented substantial variation within individual fields, with some areas acting as carbon sinks and others as strong emission sources. According to the researchers, this variability complicates climate accounting and suggests that standard emission factors may not accurately reflect conditions on the ground.

“One-size-fits-all assumptions can be misleading,” Zhao said. “More detailed measurements and more precise water-level management are needed, especially in regions where soils and farming practices vary widely.”

The findings point to rewetting as a potentially effective climate measure for cultivated peatlands in cold regions, particularly when combined with adapted cropping systems such as paludiculture, which uses plant species tolerant of wet conditions. However, the researchers caution that water management, temperature and agricultural practices must be considered together to balance climate mitigation, productivity and long-term soil health.

Enjoyed this story?

Every Monday, our subscribers get their hands on a digest of the most trending agriculture news. You can join them too!

Discussion0 comments