Researchers converted atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia using light-activated nanocrystals

Scientists have demonstrated how light-harvesting nanocrystals can be combined with biological enzymes to convert nitrogen gas into ammonia, a development that could inform future efforts to reduce the energy intensity of fertilizer production.

Ammonia is a cornerstone of global agriculture, underpinning nitrogen fertilizers that sustain food production worldwide. Its manufacture, however, is highly energy intensive, accounting for about 2% of global energy consumption. Roughly half of the world’s ammonia is produced through the industrial Haber-Bosch process, while the other half comes from biological nitrogen fixation carried out by microorganisms using specialized enzymes.

Researchers from the National Laboratory of the Rockies (NLR), working with collaborators at the University of Colorado Boulder, Utah State University, and the University of Oklahoma, investigated how light could be used to drive biological nitrogen fixation in a controlled system. Their findings were published in Cell Reports Physical Science.

The team focused on molybdenum nitrogenase, an enzyme that naturally converts atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia without the high temperatures and pressures required by Haber-Bosch. While biologically efficient, nitrogen fixation in nature is geographically dispersed, limiting its use for large-scale, centralized agriculture.

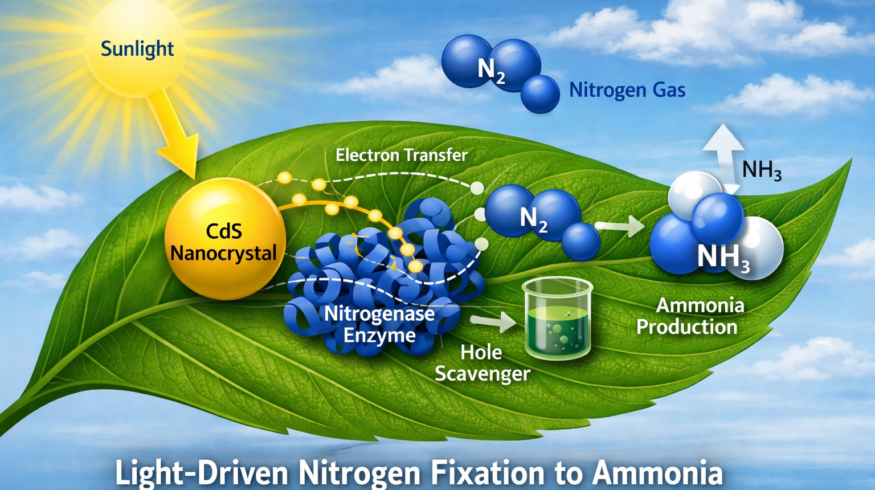

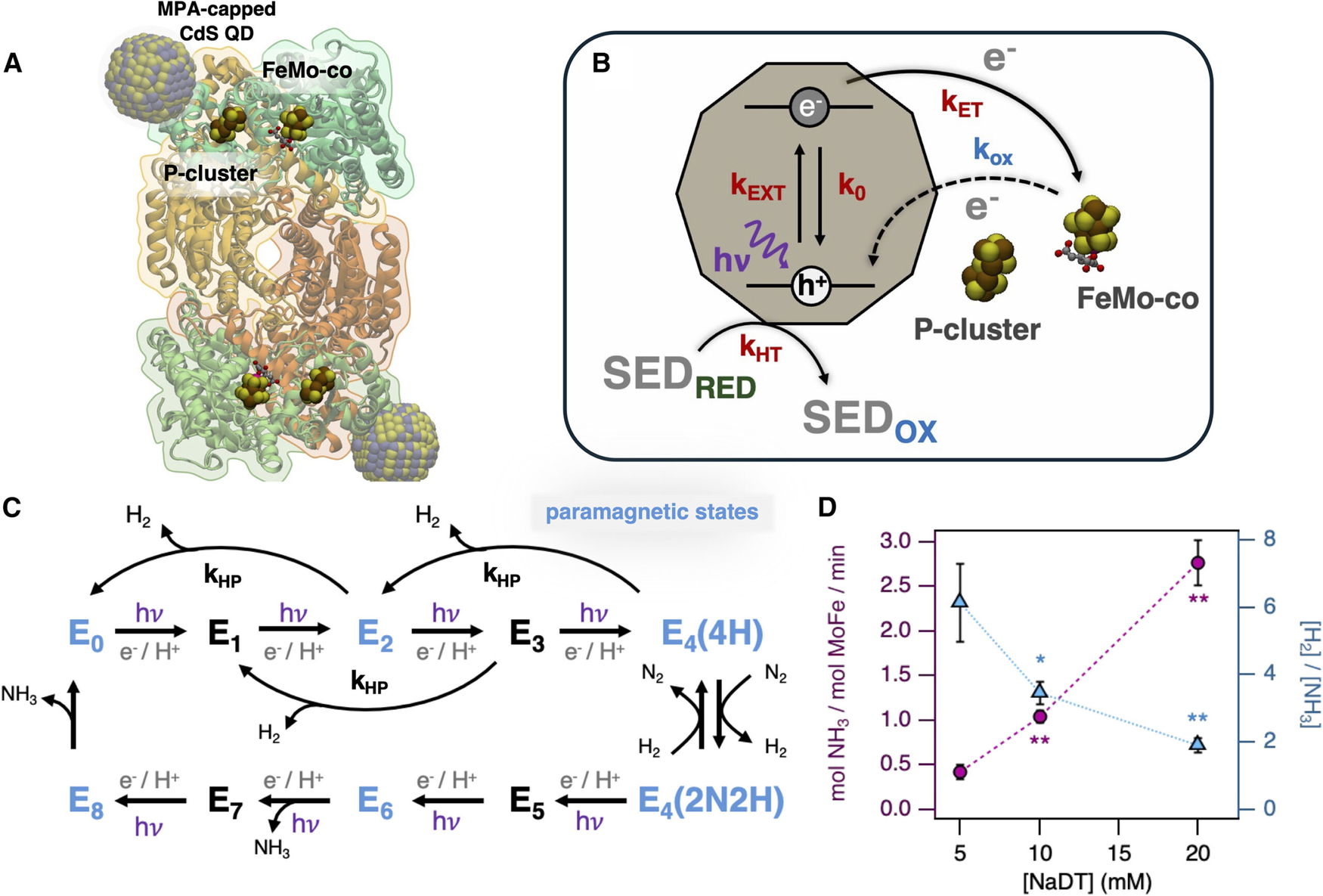

To address this, the researchers studied a biohybrid system that pairs the molybdenum-iron (MoFe) protein component of nitrogenase with cadmium sulfide (CdS) nanocrystals. In this setup, the nanocrystals absorb light and generate high-energy electrons, which are then transferred directly to the MoFe protein to drive the chemical reduction of nitrogen to ammonia.

Earlier work by the group showed that CdS nanocrystals could replace the enzyme’s native iron (Fe) protein, which normally delivers electrons during nitrogen fixation. This substitution allows light—either from sunlight or artificial sources—to serve as the energy input for the reaction.

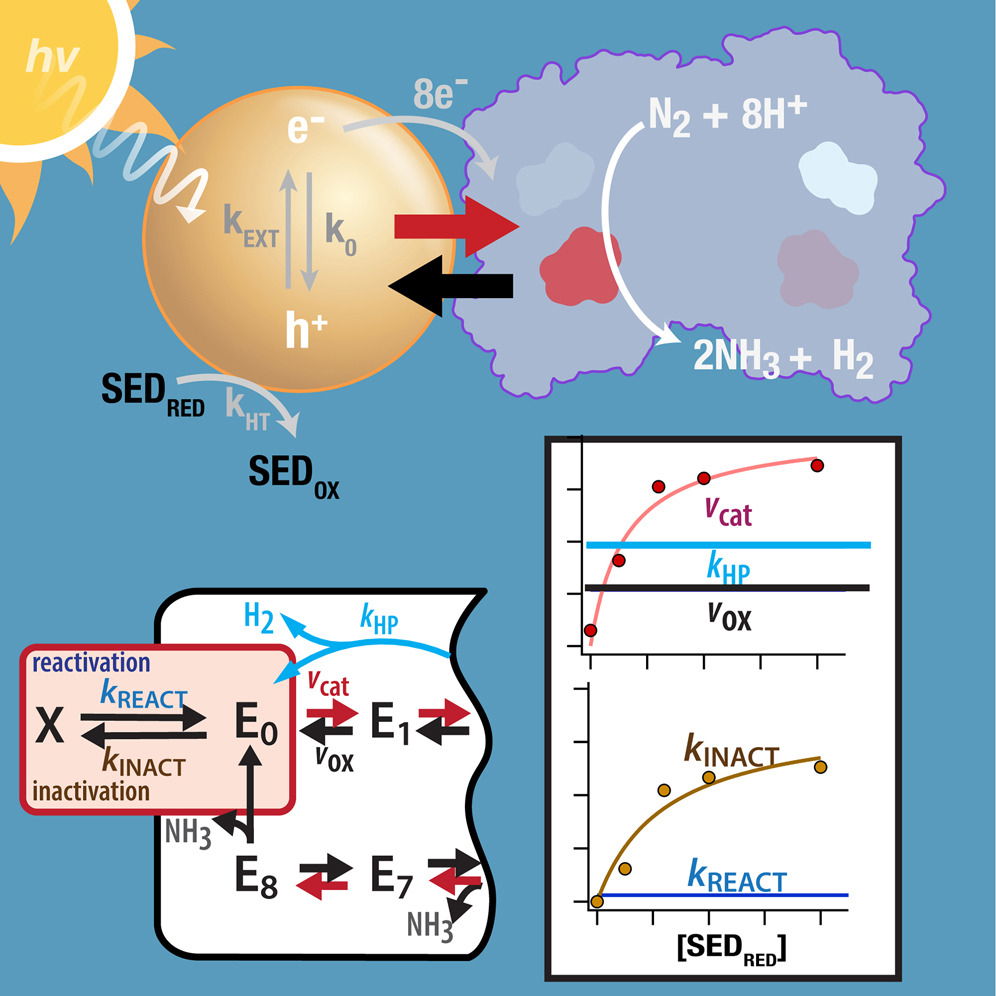

Using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy, the researchers tracked short-lived reaction intermediates formed during nitrogen activation. By partially freezing the system, they slowed the reaction enough to observe these intermediate states and map the sequence of electron transfer steps.

A key focus of the study was the role of so-called hole scavengers—molecules that neutralize the positively charged “holes” left behind when excited electrons move from the nanocrystals to the enzyme. Without effective hole scavenging, electrons can recombine with these holes or be pulled back from the enzyme, reducing ammonia yield.

The experiments showed that sodium dithionite, used as a hole scavenger, strongly influenced the rate of electron delivery and overall efficiency of nitrogen reduction. Adjusting its concentration allowed the researchers to promote nitrogen activation and improve catalytic performance.

According to the authors, understanding how electron delivery and hole scavenging govern enzyme activity could help guide the design of future light-driven nitrogen fixation systems. Such approaches may eventually enable more localized ammonia production using nitrogen from the air, potentially lowering both energy use and transportation costs.

While the research remains at a laboratory stage, it offers insight into how biohybrid technologies might complement or partially replace conventional ammonia synthesis pathways in the long term.

Enjoyed this story?

Every Monday, our subscribers get their hands on a digest of the most trending agriculture news. You can join them too!

Discussion0 comments